HY1101E: Asia and the Modern World

Discuss the following statement: “India did not exist as a nation until the British created it.” Do you agree or disagree?

India, so named after the Indus River, is home to 960 million people living in the subcontinent belonging to several races, each with their own distinct ethnicities, languages and cultures. As Ranbir Vohra observes, “they follow seven prominent religions (Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity, Jainism and Zoroastrianism) that are split by thousands of sects and castes; and they speak nearly two thousand dialects associated with fourteen well-established languages (each with its own script and literature)”[1]. With such a diversity and multiplicity of peoples living together in the subcontinent, it is hard to imagine the entire Indian subcontinent as a nation. Therefore, to say that India did not exist as a nation until the British created it seems to be a fair statement to make.

It would be useful at this point in time to define the word ‘nation’, as there are different facets and interpretations of the word itself. For the purpose of setting the parameters upon which forms the basis of my argument, I would define the ‘Nation’ as a community of people of mainly common descent, history, language, customs, ideas while at the same time inhabiting a territory and forming a state. Otto Bauer states that nation is a concept of national character, where the members of a nation are linked by a community of character in a certain definite era[2], thereby reaffirming the validity of my definition.

The history of India in the pre-colonial period has been everything but austere. A myriad of civilizations and empires flourished and dwindled into oblivion in a series of cycles of power between the periods 2600 B.C., where the earliest known settlements were established in the form of the Indus Valley civilization till the collapse of the Moghul Empire in 1785 A.D., which at the same time, heralded the start of direct British involvement in the administration of the entire subcontinent. The Indus Valley civilization, which lasted from around 3000 B.C. till about 2000 B.C., was the first ever known civilization located in the Indian subcontinent. With the abrupt end of the civilization and the coming of the Aryans to succeed the dominance in the Indus plain and beyond, a multitude of empires arose. Amongst the most prominent in the North were the Mauryan Empire and its famous Emperor Asoka, as well as the Gupta dynasty and its Gupta monarchs; in the south, the Pallava Kingdom and the Chola Empire held reign not only in the southern peninsula, but also till the far reaches of Southeast Asia. With the rise of Islam around the 7th century A.D. came the establishment of Muslim kingdoms in the North, which saw the coming of the Turco-Afgan paramountcy[3], under the banner of Muhammad Ghuri in 1192, who defeated the Hindu Rajaputs and paved way for the ascent of Muslim sovereignty and much later, the Moghul Empire.

However, to say that these empires gave birth to the Indian nation would be a fallacious remark. The Indus Valley civilization is regarded by some scholars as the cradle of civilization in the subcontinent. Artifacts such as terracotta seals, clay figurines, adornments of gold, silver and other fine materials[4] presents enough evidence of a thriving culture and tradition. However, its boundaries never extended beyond the Indus plains. Notwithstanding, there had been many great dynasties in pre-colonial history that had ruled the subcontinent, but none had ever unified the peoples of the land under a single empire. The monarchs of these great kingdoms in pre-colonial India did seek to establish sovereignty over the entire subcontinent. Asoka of the Mauryan Empire came close, under which his empire stretched from the Hindu Kush mountains till the Bay of Bengal, with the subjugation of the Kalingas (occupying today’s Orissa on the Bay of Bengal), but left the southern peninsula, where present day Madras and Bangalore lies, independent of his rule[5]. The same could be generally said for the Gupta Dynasty and the Moghul Empire, whom though controlled much of the north and central parts of the landscape, never did conquer the entire subcontinent. Geographically at least, a unified Indian nation had not existed then.

It is important to note that the peoples of India never regarded themselves to be of the same race. The names they use say it all: Aryans and Dravidians; Gurjara-Pratiharas, Palas and Rashtrakutas; Paramaras, Chandellas and Chedis[6], to state only a few. Divided by differences in language, religion, culture, ethnicity and political affiliations, the peoples of India lived alongside and fought with each other, constantly seeking a state for their own, or forging a dominant kingdom over the others. The kingdoms and empires of the subcontinent has always been that of conquests and subjugation, never of assimilation and cohabitation. Nonetheless, the peoples of the subcontinent never did recognize themselves as members of the same nation and fought each other just as hard as enemies of separate countries.

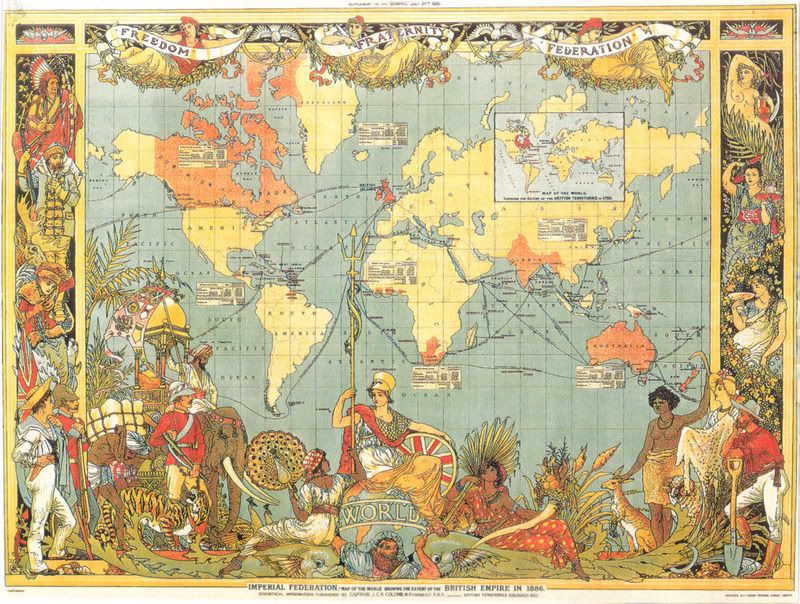

The British presence in India started as a modest factory at Surat in 1611 with permission from the Moghul governor and expanded into a British Empire unifying the entire subcontinent by 1876 when Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India. For the first time in Indian history all the states were under one administration, under the British Crown. As written by Bridwell-Bowles, colonial powers imposed often artificial boundaries and nation status on the lands under their domination[7]. With this annexation of former Hindu and Muslim states into British territory, it bore the seeds and set the boundaries of a new unified country. The geo-political barriers that were broken down by the British and the unification of the subcontinent under the British through the various wars had demolished regionalism in India[8].

Britain, with the power of a century of industrial revolution behind them, fuelled by imperialism, made unprecedented structural changes to the subcontinent in order to meet the demands of capitalism. To satisfy the infrastructural needs of the economy, trade, market and communication network were established[9]. For example, roads, railways and the postal service were introduced under British administration. Port-cities built up to boost trade eventually developed into large modern towns or cities. A common standard of currency, the Indian Rupee, was introduced under the crown government. The British also laid down the foundation of a new judicial system by establishing a hierarchy of civil and criminal courts, started by Governor-General Warren Hastings[10], thereby introducing a new system of justice and law in India. All these factors though were meant to serve the purpose of an efficient colonial administration, but it laid the groundwork for a unified Indian nation by bringing the indigenous people closer to each other and a common feeling of nationality.

One of the most important aspects of the structural changes implemented by the British was the introduction of Western education to the indigenous people of the country. In order to supply the manpower needed to fill the lower bureaucratic jobs in the administration, schools and colleges orientated to Western education were established such that the indigenous people could be trained and work for the British. This process of transformation brought about by British colonialism caused its subjects to be exposed to European ideas such as liberalism, rationalism, progress and nationalist thoughts[11]. As a result, the British had unintentionally created a new generation of Indian intellectuals who believed strongly in these European ideals and European discourses of progress, and believed that such a progress could be implemented in their homeland. For the first time Indians all over the country regarded themselves as subjects of the same country, working not for different Sultans or Rajas, but for the general interests of everyone under the British administration. These educated Indians would then form their own nationalistic movements, such as the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League in a bit to oust British colonial rule and campaign for self-government, an ideological foundation for the Nation of India.

The constitutional developments in colonial India also played a part in forging the Indian Nation. Prior to the Indian revolt in 1857, the indigenous people had no say in the running of the colony. With the Indian Councils Act in 1861, it marked the beginning of the policy of the British which was called ‘the policy of association’ or ‘the policy of benevolent despotism’ because an attempt was made to include the Indians in the administration of the country[12], by including them as members in the Executive Council of the Governor-General. Subsequent reforms and acts were gradually implemented by the Crown[13] due to increasing pressure from Indian nationalist movements such as the Indian National Congress and its leaders, the most prominent being Mahatma Gandhi, which gave Indians more executive powers in the administration of the colony. Finally in 1947, the Indian Independence Act was passed by the British parliament which led to the creation of the independent state of India.

It was never the intention of the British Crown to create an Indian nation as the final phase in colonial rule. On the contrary, colonial administration seeks to undermine nationalist sentiments by segregating society into different social groups[14]. In the Modern World System as proposed by Immanuel Wallerstein[15], the colony functioned as a peripheral state to provide natural resources and labor to the political and economical core state of Britain. However, due to the structural changes and unification of the geo-political landscape of the subcontinent, as well as the exploitation of resources and labor of the colony of India, dissention of the people arose as more Indians become educated with the implementation of Western education, creating a call for anti-colonial movements which sparked a general wave of Nationalism. Though only as a solution to appease the problems the colonial office was facing, it can be concluded that the British had inadvertently created the Indian nation.

[1] Ranbir Vohra, The Making of India: A Historical Survey (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. 1997), pp.17.

[2] Gopal Balakrishnan, Mapping the Nation, pp.40-41.

[3] Francis Watson, India: A Concise History (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2002), pp.95-104.

[4] Francis Watson, India: A Concise History (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2002), pp.26-27.

[5] D. A. Girling, New Age Encyclopedia, Book 15, HYD-ITA (London: Bay Books), pp.97.

[6] D. A. Girling, New Age Encyclopedia, Book 15, HYD-ITA (London: Bay Books), pp.97.

[7] Lillian Bridwell-Bowles, Identity matters: Rhetorics of Difference, pp.507.

[8] Sajal Nag, Nationalism, Separatism and Secessionism (Rawat Publications, 1999), pp.22

[9] Sajal Nag, Nationalism, Separatism and Secessionism (Rawat Publications, 1999), pp.21.

[10] L. P. Sharma, History of Modern India (Konark Publishers PVT LTD, 1990), pp.196-197.

[11] Sajal Nag, Nationalism, Separatism and Secessionism (Rawat Publications, 1999), pp.21.

[12] L. P. Sharma, History of Modern India (Konark Publishers PVT LTD, 1990), pp.327.

[13] L. P. Sharma, History of Modern India (Konark Publishers PVT LTD, 1990), pp. 329-346.

[14] Sajal Nag, Nationalism, Separatism and Secessionism (Rawat Publications, 1999), pp.18-19.

[15] Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System (New York: Academic Press, 1974-)

References:

1. Ranbir Vohra, The Making of India: A Historical Survey (New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. 1997)

2. Gopal Balakrishnan, Mapping the Nation

3. Francis Watson, India: A Concise History (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2002)

4. D. A. Girling, New Age Encyclopedia, Book 15, HYD-ITA (London: Bay Books)

5. Lillian Bridwell-Bowles, Identity matters: Rhetorics of Difference

6. Sajal Nag, Nationalism, Separatism and Secessionism (Rawat Publications, 1999)

7. L. P. Sharma, History of Modern India (Konark Publishers PVT LTD, 1990)

8. Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System (New York: Academic Press, 1974-)

No comments:

Post a Comment